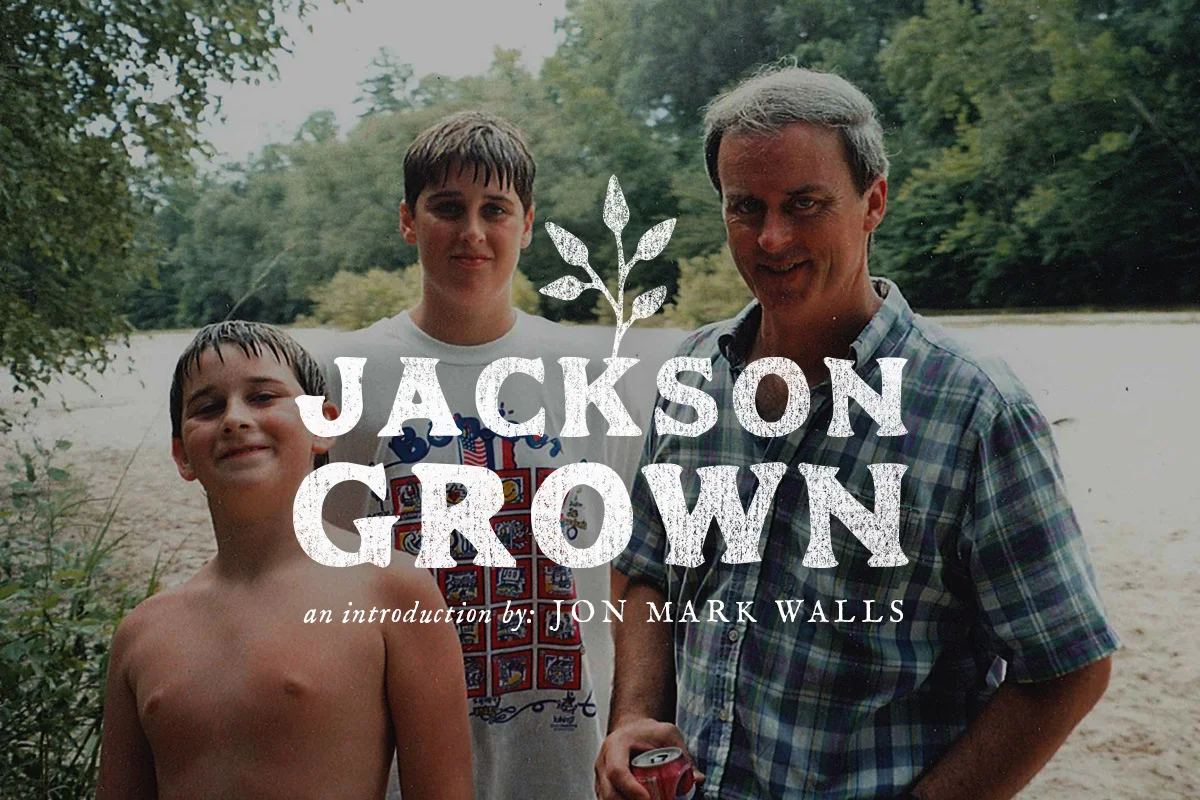

Jackson Grown: Drew Sutton

Long Shot: How a former middle of the road player from a mid-sized town finds his game and a way to the biggest show in baseball.

A sharp, deep crack resonated across the emptiness of the gymnasium. I could hear the sound from the hallway as I walked through the doors and up the stairs. I was not there early enough.

“Thwack.” A slow, echoing return to silence. A moment’s pause.

“Thwack.” Dilution into quiet, another pause.

“Thwack.”

The batting cages of Union University were used for winter practice by the university’s baseball and softball teams and were often left empty in the odd hours. Because our mothers worked there, we had both independently assumed a never confirmed permission to tweak our hitting mechanics when no one was around.

Every once in a while we would pass each other on our way in or out, squeezing in a few extra swings for the evening — a look up, a wipe of the brow, a nod, a tightening of the batting gloves, and an “almost done.”

Drew Sutton and I were skinny, rival players with more or less realistic hopes of playing baseball for a low to mid-level university... somewhere.

We played on opposing high school teams. Two years older and twenty pounds lighter, Drew was a slightly above-average senior player on a far above average team. North Side High School is a typical thousand-person public school nestled comfortably in the middle of a mid-sized town in a mid-sized state in middle America.

Between 1998 and 2002, North Side fell upon a chance constellation of star baseball talent. Steered by a fiery coach, the team produced multiple professional draft picks for teams including the St. Louis Cardinals and Atlanta Braves as well as signees with top-level universities such as the University of Mississippi, University of Tennessee, and Auburn University.

A PLACE TO START

By the end of his final high school season, Drew’s offers were late, minimal, and weak. “I saw guys on our team getting dream scholarships and signing impressive bonuses from professional teams. After graduation, I still didn’t know where, or if, I was moving up,” Drew remembers. The only real opportunity came from a small junior college in an obscure town stretched across Texas and Arkansas state line.

“I was a weaker, skinnier version of a good player. They could see I knew the game, had some skills, was a good teammate and was willing to work,” Drew recalled. “For them, I guess that was enough. And all I wanted was a chance.”

Baseball is a unique game, one that offers both literary beauty and mathematical symmetry. It is one that has woven itself into a century and a half of American culture. As are many of the most significant cornerstones of the country's identity, the genetics of baseball have been both drivers and reflectors of American myth and reality. Like foul lines running between home plate and the outfield walls, there are distinct, but very easily blurred lines between that legend and truth. One of our country’s best, most enduring (and debated) myths is the idea that with the right amount of work and sacrifice anyone can, however it may be defined, “make it”.

One of our country’s best, most enduring (and debated) myths is the idea that with the right amount of work and sacrifice anyone can, however it may be defined, “make it”.

Jon Mark Walls

For each of the thirty Major League Baseball teams in cities like New York, Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles there are seven levels of professional teams below the headline club which compete in affiliated minor leagues. In what has often felt like a baseball purgatory for players, just outside the gates of utopia, these lower leagues represent nearly 9,000 minor leaguers scraping together existences in towns such as Ogden, Hagerstown, and Altoona. Towns where Ramadas replace Four Seasons, old chartered buses replace chic chartered flights and 120 dollar weekly food allowances replace 120 dollar lunches.

Many players struggle on 8,000 dollar-per-year salaries grasping to dreams fueled by stories of an R.A Dickey or Jamie Moyer jumping to the big leagues after years of toiling. Many are one sprained ankle or shoulder injury away from moving up the ladder. The dream is addictively alluring and frustratingly distant.

Nestled in the crevice of a border town with an economy driven, in large part, by an Army ammunition storage facility, the Texarkana Junior College baseball program had a surprising reputation for sending players to higher collegiate and professional levels. It was both a holding pin for players waiting for the pro draft and a single track training facility for those wanting to move up.

“Whereas a number of my high school teammates were playing in the minor leagues or contributing to some of the best baseball programs in the country, they only were able to play 20-30 games in the Fall and the Spring.” Because of looser restrictions at the junior college level, Drew was able to refine his skills and build on areas he needed to improve over roughly 150 games his first year.

“I simply got more experience. We also had a pretty grueling training program. I gained more body mass, got stronger, and started to grow into what talent I had. I was also able to learn how to play a number of positions which helped me become a lot more adaptable. In short, I became a student of the game and began to understand myself. I was not a lightning-fast base runner or a huge power hitter. I had a good arm, not a great arm but could play defense relatively well. Importantly, I learned what my game was and how to adjust for areas where I wasn’t as strong,” he said.

After two years at Texarkana, Drew signed to play with Baylor University, a top NCAA Division I program. The level was a jump. “There though, I eventually had the same realization that I had when I played in high school and then my year at junior college,” he said.

“At some point in the seasons, despite doubts, I looked around and saw that I could play and actually compete pretty well at the level I was in. I had never been the best on any of the teams I played on, but my goal was to compete and contribute wherever I found myself,” Drew recalls. If there were any aspirations for the next level they stayed quiet.

MAKING IT

Simon Sinek, the made-famous-by-TED author, speaker, and motivation guru, estimated that roughly 20% of people feel that they have “made it” in their respective areas and are living their dream job.

Reasons vary for the low percentage. Some cite barriers, internal and external, some controllable and some not. People emphasize responsibility, genuine or dubious. Others highlight risk aversion, fear, indifference or lack of ambition, imagination or ability.

For the 132 million people in the American labor force who, to varying degrees, endure their 8 to 10 hours-per-day invested in work, it is worth reflecting on what has prevented that large, diverse group of individuals from being able or willing to define, articulate, consider and pursue a dream whether that be career-related or otherwise.

As in most of the highest professional levels, whether medicine, engineering, law, academia, or business, Major League Baseball requires an above-average degree of natural talent, diligence, awareness and composition. Those requirements however do not ensure entrance into those elite arenas.

It is, rather, perhaps a safe bet to acknowledge that context, coincidence and chance have as much sway on the outcome of one’s ambition as one’s ethic or talent. It is equally as likely that the most honest of the big dream achievers would, with a perplexed nod, agree.

“It seems like a crazy mistake that I outlasted somebody,” he said with a chuckle. Drew’s navigation of the corn maze of paths to the Major Leagues saw rise and fall up and down the ladders of organizations. He was packaged with dozens of other players and traded laterally and diagonally across teams. One jersey one day, another the next. In one year, five cities off the field and six positions on it. He received multiple forms of contracts and players agreements, some barely meeting minimum wage. He slept in barren, off season apartments eating takeout on lawn furniture dreaming with other minor leaguers about the season to come. Fuel replacing dollars not earned.

Most would chip away for a few years in the lower minor leagues before reality set in, tipping their hats to the game and moving on.

A REASON TO DREAM

Built in 1912, Fenway Park is the oldest active stadium in Major League Baseball and home of the storied Boston Red Sox. The Elysian field for baseball enthusiasts. On July 4, 2011, Drew stood at the base of the Green Monster draped with an immense American flag. Timed to perfection with the final notes of the national anthem four American Air Force F-16 jets flew over the thirty-seven-foot wall overlooking left field. The 37,305 fans in the sold-out stadium roared.

Drew looked up, smiled, glanced at his teammates next to him, and jogged into the dugout. It was time to play ball.

“There were many moments where I just shook my head, sent up a little thank you and had to focus on getting to work. That was certainly one of them.” Drew said.

In that third Major League Season playing for one of baseball history’s great teams filled with legendary players, Drew achieved a batting average of .315, the universal mark of excellence for hitters. “For me, that was important, to be able to say that I had truly competed at the highest level. To do it with that team with experiences like that, unbelievable,” Drew said.

Over the course of his four years in the Major Leagues, Drew played for six Major League teams. He hit game winning, fireworks inducing home runs for the Pittsburgh Pirates, snuck in the back entrances of hotels to escape screaming fans and became golf buddies with baseball icons like Chipper Jones.

“I just showed up, same in the big leagues as it was in high school. I asked myself what I wanted to work on each day, did it and just tried not to give the coaches any reason not to put me on the field,” Drew smiled, “This time though, I didn’t have to slide a driver’s license through the crack in the door to get into the batting cages.”

“I just showed up, same in the big leagues as it was in high school. I asked myself what I wanted to work on each day, did it and just tried not to give the coaches any reason not to put me on the field”

Drew Sutton

His career was marked by exceptional versatility. A player that could play six positions and hit both right handed and left handed, Drew exemplified adaptability in an arena where the world’s best players spend careers finding and perfecting narrow niches.

In its 145 year history, Drew Sutton was the 17,199th player to play for a Major League Baseball team, an elite club composed of names such as Babe Ruth, Jackie Robinson, Ted Williams, and Lou Gherig.

His is a story of achievement grounded in an alluring, approachable, and balanced blend of skill, hard work, chance, and a willingness to imagine. Importantly, it underscores the required humility and patience as well as the ultimate value of understanding and appreciating one’s unique talents wherever those might fall.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, his story serves as a foothold for dreaming beyond artificial expectations and seeing the untameable nature of circumstance as a reason to dream as opposed to blocking oneself from it.

A native of Jackson, Jon Mark Walls is a social entrepreneur, lecturer, and speechwriter who is driven by the idea that better communication can lead to better politics. Having worked for the United Nations as well as various governments and NGOs, he co-founded GovFaces which aimed to improve interactive communication between citizens and representatives. Based in Geneva, Switzerland, Jon Mark has sought to blend traditional communications approaches with new technologies and develop ways of delivering ideas across all levels of society.