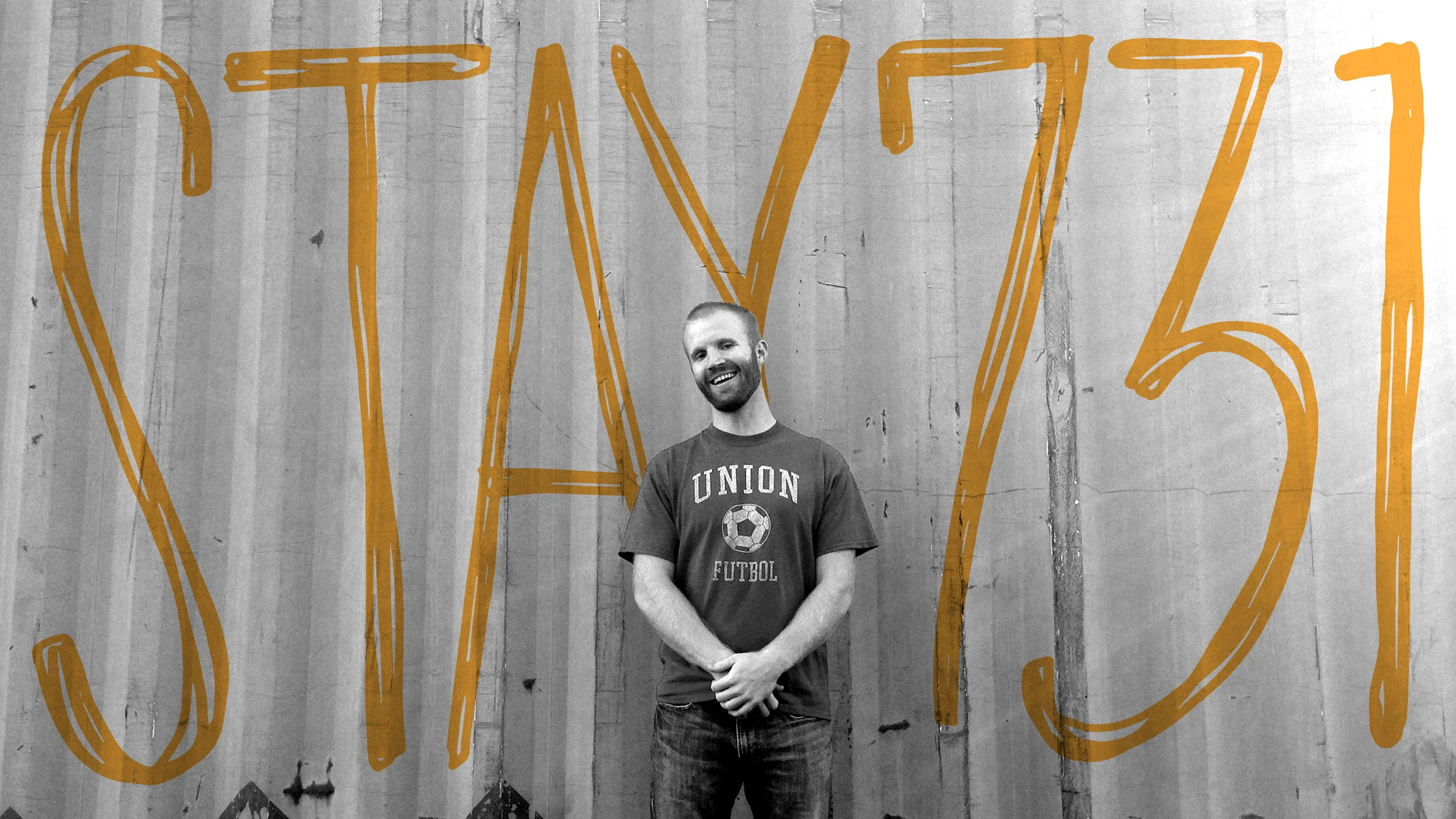

Stay 731: Roots

I got my first tattoo when I was twenty-three years old. I worked for it, too. I was married at the time, and it took me two years to convince my wife that I should have one. I guess the compromise was that it would be a cross, which was hard for her to argue against. I picked the cross off of a poster-sized print hanging in the tattoo shop. The design was “flash,” which is a stereotypical design of a tattoo, but I didn’t know that at the time. I knew I wanted a tattoo, so I picked one out. Unfortunately Justin Timberlake showed up in an NSYNC video a few months later with the same tattoo I had, so whatever badass appeal I thought I had attained instantly evaporated.

Over the next several years I would accrue several more tattoos. Most of them I would design myself or collaborate with an artist. Each of them were significant for the particular time in my life, though I didn’t necessarily think about that when I was getting them. A conversation with a friend a few months ago brought it to my attention. When I see the ink on my body, I’m reminded of the time when I got that particular tattoo. The cross on my arm reminds me of Chicago, which is where I was when I convinced my wife to let me get one. The star on my shoulder reminds me of my daughter because she was just a baby when I got it. The crows on my back remind me of the hardest year of my life because it was the year I went through a divorce. The symbol on the inside of my left wrist makes me think of a person who probably knows me better than anyone else because she got one the same night. My most recent tattoo, a red lightning bolt, makes me aware of the potential of whatever the future may bring because it’s the center of what I hope will become a larger piece of art on the inside of my right bicep and eventually trail to my forearm. The ink is permanent and so are the memories associated with them.

Memory is tied to everything in my life. Sometimes I wish my memory wasn’t as good as it actually is. Often I feel that I haven’t forgotten anything and that every experience I’ve had is permanently carved into my brain—a mental tattoo, if you will. In reality I know that there are things that have slipped away over time; they have been filed away somewhere deep in my subconscious. But the ones that have stayed—the experiences, the people, the emotions—those are all associated with one place.

When I come to the end of Russell Road, driving north, I see Andrew Jackson Elementary School, and I immediately think of my dad driving Autumn Thompson (my neighbor) and me to school every morning. If I happen to be heading north on Highland and see the intersection of Old Humboldt Road, I think of a Friday night after a football game, heading to my friend Drew’s house for a party. There are times I’m driving south and pass what used to be a used car lot where my parents bought me my first car. I can’t help but think of how bad that car turned out to be. Every place and every street is tied to a memory, and memories and experiences create who we are as people. The city of Jackson is synonymous with every experience in my life because it’s the only place I have ever lived.

“Every place and every street is tied to a memory, and memories and experiences create who we are as people.”

In 2008 I went through a divorce, and my ex-wife and my daughter moved to Plano, Texas. Plano is a suburb (in every sense of the word) of Dallas. There are endless rows of strip malls and homogenous subdivisions. If soccer moms and mini-vans had a capital city, Plano would be that city. The demographics of Plano skew heavily Caucasian, and the concrete is suffocating. For a long time I tried to reason with myself what it would take for me to be comfortable moving down there. In the spring of 2009 I took resumes to every middle school in the town. I looked at apartments and even tried out a few gyms, but nothing felt like home to me. I began to build rationalizations of why I could wait to move there, but the reality of the situation was that whatever that town held, it wasn’t Jackson.

After my divorce my daughter spent a week every month here in Jackson. I lived in an apartment on the north side of town. Our memories began to be burned into that place. As she grew older, she would ask me each time we talked on the phone when she was coming to Jackson again. She began to feel a connection to this town. Even though I lived north of the interstate, my parents still lived in midtown, and we would visit them often when she was here. We would walk to the top of the parking garage and look south over the tree tops. We would visit Campbell Lake and feed the geese . . . and then run from them because they were crazy. She and I would revisit all of the places that were branded into my mind. My memories began to be her memories. Her experiences began to be tattooed into her memory, much as mine were when I was her age.

The spring before her kindergarten year I decided that it was time for me to leave Jackson and move to the Dallas area. I knew my daughter would no longer get to spend a week every month here because she would have school. I also knew that I couldn’t be a summer and holiday father, so my only option was to move. I didn’t really think too much about it while I was going through the process. I kept my head down and plowed through every application to every school district in a forty-mile radius of Dallas. I went to interviews and had a couple of prospects, but nothing seemed to pan out.

“The idea of obligation mixed with guilt can be a powerful poison to your psyche.”

In May my parents and I took my daughter to Disney World. The first day we were there I got a call from a school in Fort Worth offering me a job. As soon as they did, my heart sank and my stomach clenched. I wasn’t sure why. The juxtaposition of being at Disney World and the sinking feelings I had about moving were a toxic cocktail. I couldn’t sleep for more than two hours each night. I would wake up with my heart racing and terrible thoughts flashing in my head. During the day I’d try my best to push my situation to the back of my mind and enjoy being with my daughter at a very special place. One afternoon while my daughter slept I went into my parents’ hotel room and told my dad about the conflicting feelings I had.

The idea of obligation mixed with guilt can be a powerful poison to your psyche. I had never considered this type of emotional reaction to leaving my hometown because I was convinced that there was no other option. My daughter was starting kindergarten, and I needed to be where she was. The reality of my situation was much different than whatever perceived obligation I believed I had. I tried my best to explain this to my dad, and he listened while I blubbered my way through what I was feeling. He tried his best to respond to what I was saying, and honestly I don’t remember most of what he said, but the one thing I do remember him saying kick-started the process of coming to terms with what my situation actually was: “What you’re feeling is normal. You have roots here. Everything you’ve experienced is in Jackson.”

I hadn’t even begun to process the way this town had shaped who I was as a person. My entire family was here. Any meaningful experience I had ever had was within the context of Jackson. If I had a memory from my childhood, it was more than likely attached to this town. As much obligation as I had to my daughter in Plano, I also realized I had to process and prepare myself to leave everything I had known—and do it alone. I called the school in Fort Worth and told them that I wouldn’t be taking the job. What followed was a severe bout of guilt, followed by a few months of intense sadness. When I finally came out of that, though, I was ready to face the reality of where I was.

“Being honest with myself was more important than what I believed my obligations were or what I thought other people thought I should do.”

Over the last three years, I’ve become more invested in this town than I have ever been. The most important thing I learned throughout this entire process was that being honest with myself was more important than what I believed my obligations were or what I thought other people thought I should do. For four years I had been afraid to invest here because I told myself I would be leaving eventually. After turning down the job in Fort Worth, I was free to really look at how I fit into what this community was trying to become. I also had to figure out how to be involved with my daughter regularly when she lived two states away.

I drive to Plano every other weekend now. I guess I’m trying to get some new ink on my brain down there. I explore every town close to there, trying to get a feel for what I think is familiar. One December Friday I happened upon a town called McKinney. There was a vibrant downtown court square and old homes in the surrounding neighborhood. It was unlike any town I’d seen in the Dallas area. It reminded me of Jackson—specifically the midtown area. When my daughter and I drove through the town the other day, she said, “This looks just like Jackson. Let’s go to your house!” She and I talk about the possibility of me moving down there, but she says she doesn’t want me to. She says she loves Jackson and that she wouldn’t get to come here in the summers and holidays if I lived down there. I know there will come a day when that will change. She’s eight years old now, but she won’t be eight forever.

Sometimes I wonder why I stay here. There are plenty of frustrations to be seen within this town. The same people from the same demographic make the rules and the decisions for all of us. Most recently we’ve decided to close schools and expand the prison. It’s a decision so asinine that it makes me wonder in what decade we’re actually living. We’re segregated, politically top-heavy with rich white people, and socially stunted. However there are pockets of resistance to the things previously mentioned. I see people in our town who value art and analytical thinking. There’s a burgeoning culture of a generation who truly wants racial reconciliation. There’s an investment in our downtown area. Some would call that gentrification, but I call it a chance to for people of different economic classes to be together. There is so much potential here now, but potential is only an abstract idea. The reason I stay, for now, is because I am tied to this town like so many other people that were raised here and have their memories rooted in the ground that is Jackson.

“The reason I stay, for now, is because I am tied to this town like so many other people that were raised here and have their memories rooted in the ground that is Jackson.”

There will come a day when I will more than likely leave Jackson, but right now I like being part of the push to make Jackson what I know it can become. Nostalgia can be deceptive, but I do remember a time when our public schools were diverse and thriving. I can remember a time when we weren’t as racially segregated as we are now. Most change is generational, and I love that my daughter can experience what Jackson looks like compared to the suburb where she spends most of her time. I love that she can see the changes that I see this town beginning to make.

I stay in Jackson because we are irrevocably linked. Jackson is much more than a town to me. It’s an entity that lies just beneath my skin and runs in my blood. It’s a tattoo that’s rooted beneath the surface. Even when I leave this place will stay with me because it’s in my blood, it’s in my brain, it’s in my soul. While I’m here, though, I will do everything I can to help make Jackson a community that feels like home to everyone. I will share my story of what I knew Jackson to be and what I know Jackson will become. And I know I can tell that story with authenticity because its story is my story.

“While I’m here, though, I will do everything I can to help make Jackson a community that feels like home to everyone.”

Gabe Hart is an English and Language Arts teacher at Northeast Middle School. He was born and raised in Jackson, graduating from Jackson Central-Merry in 1997 and Union University in 2001. Gabe enjoys spending time and traveling with his daughter, Jordan, who is eight years old. His hobbies include reading, writing, and playing sports . . . even though he’s getting too old for the last one. Gabe lives in Midtown Jackson and has a desire to see all of Jackson grow together.

Header image by Katie Howerton.